Hi everyone,

Today I’m here to discuss something technical, but hopefully in an inspirited way: sidereal and tropical measurements of the lunar stations. This will be the first entry in a two part series answering the question: should we use tropical or sidereal coordinates when working with the lunar stations? The first answer will be a historical one; the second answer an esoteric one.

This question is contentious and convoluted. On its surface it is often summarized simply: in Jyotish, they use the sidereal zodiac for everything and in Western astrology, we use the tropical zodiac for everything.

As the mainstream discourse seems to go amongst English-speaking astrologers, the mansions have basically always been used following the tropical zodiac by astrologers west of India, with station 1 (Sharaṭain) starting at 0º tropical Aries. Case closed.

But is this actually true?

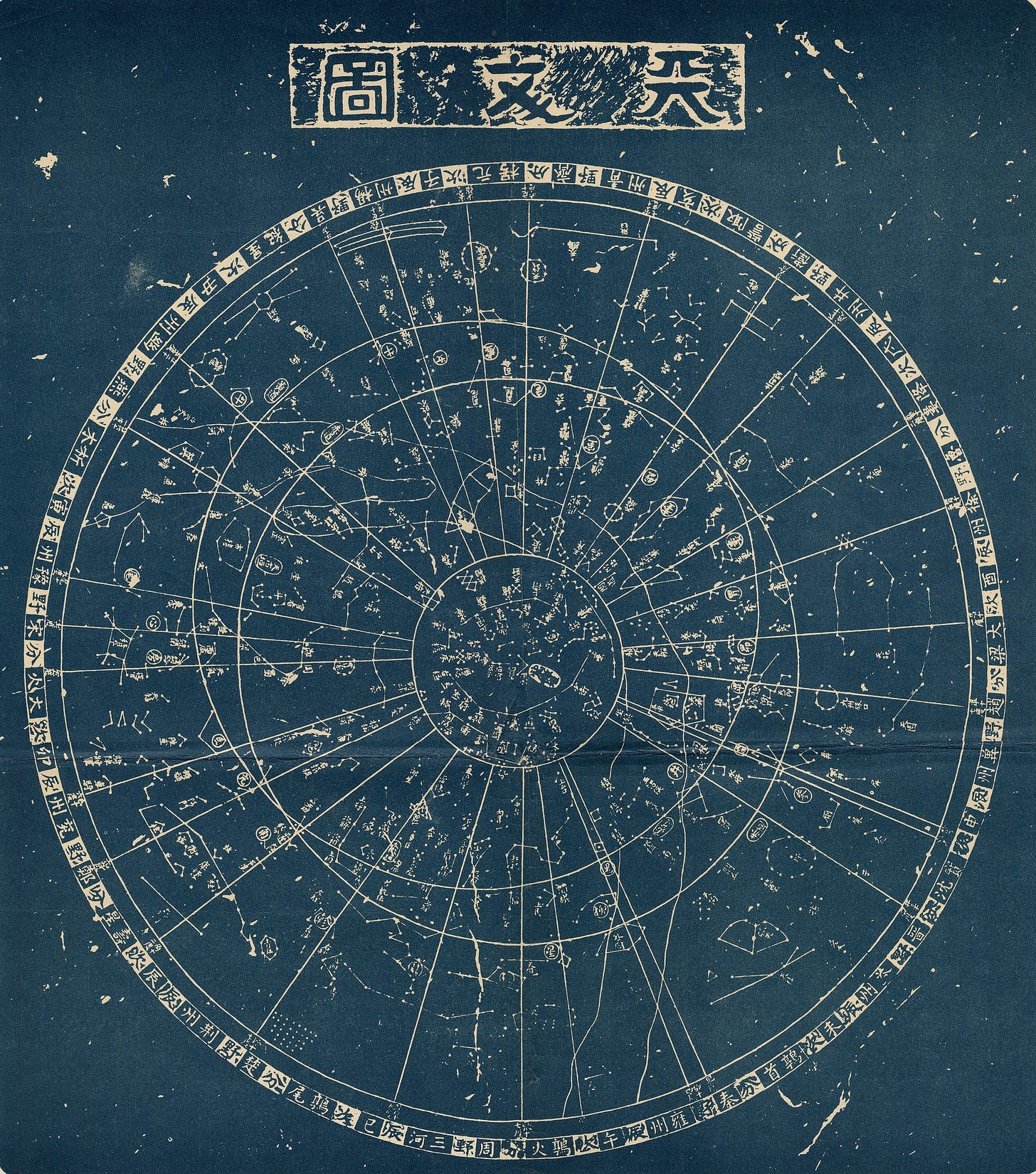

To summarize what is an extremely complicated topic, Chinese and Indian astronomers have a well-established tradition for interaction with their lunar station systems. There is extensive debate about which of these two cultures innovated the system of the lunar zodiac, but both systems are extremely ancient and important to their respective cultures. Let’s leave it at that. The Indian astrological approach is very straightforward, using the sidereal zodiac (typically using the Lahiri ayanamsa but not always) for their measurement of the 12 signs of the zodiac and their 27 nakshatra नक्षत्र.1 The Chinese approach to the ecliptic is much more complicated (and Chinese astrology seems to be less invested in the ecliptic specifically than Indian or Greco-Islamicate western astrology). My understanding is that they traditionally use a tropical zodiac, but then draw boundaries for their xiù 宿 based on the positions of their indicator stars (so, using a sidereal system). The xiù, at least in their most canonical form, also use what is sometimes called a “constellational” approach, in which each station’s size varies depending on how close or far the various indicator stars are.2

Those who specialize in such things tell me that the Sassanian Persians used a sidereal zodiac and that the stations as a formalized system likely emerged into Arabic-speaking culture through the bridge Persian culture formed with the civilization of India.3 So, at least at the beginning, the stations we’re discussing were calculated sidereally.

It seems like this question of sidereal vs tropical haunted astrologers for centuries. What a relief! We’re surrounded by ancestors.

I found that Abraham ibn Ezra, a Jewish astrologer-rabbi from Spain, argued for a constellational approach to the stations (just about the same as the Chinese one described above) or at least a sidereal approach, even though he used the tropical zodiac for everything else.4 Ibn Ezra’s argument is essentially the same as mine: if the lunar stations are defined by certain stars, shouldn’t we be interpreting them by the Moon’s physical presence near the stars? Ibn Ezra was highly educated in the Arabic language and made the important observation that most of the names of the stations were identical to the names of their stars (or otherwise directly referenced them). Hundreds of years after the fall of the Sassanian Empire, across the world, the idea of the sidereal stations hadn’t died out.

Ibn Ezra lived and wrote in the Islamicate cultural milieu of the medieval Iberian peninsula, so maybe part of his approach was focused on his own Arabic scholarship? Even that doesn’t seem to be the case: I’ve found intimations of sidereal/constellational station systems in popular astrological textbooks in late-medieval/early-renaissance Europe, written in languages like German and English.5 Note that this phase of the astrological tradition in the late 1600s represented some of the very tail end of “traditional astrology” until its revival in the 20th century. From the earliest introduction of the lunar stations to some of their latest iterations, astrologers have asked continuously how to integrate the stars into our judgements.

The idea that so-called Westerners have always used only the tropical stations is a myth. It is has been an ongoing conversation all along.

Both / And instead of Either / Or?

There are reasonable theoretical arguments for both the sidereal and tropical stations. As I’ve said above, I am personally inclined to agree with ibn Ezra that it makes the most sense to ground the stations in their indicator stars. This is the primary theoretical push of the project I am presenting, and I want to advocate for it considering that it seems to not be the mainstream perspective.

I don’t want to pretend that the tropical stations are without merit, though.

One of the primary uses for the stations in Arabic-speaking cultures are their connection to weather and the seasons. The anwā’ • أنواء are groupings of stars associated with the bringing of seasonal rains6, which are of vital importance for the inhabitants of the arid environments of Mesopotamia and the Arabian Peninsula. As I understand it, these stars were grouped together something like parans with one star/asterism having its heliacal set at the same time as another star/asterism had its heliacal rise on the other side of the sky.7 In other words, these stars are on opposite sides of the sky and either rise or set at (roughly) the same time. They’re bound together not by actual proximity but rather the fact that the transition heliacal phase around the same time of year. The setting stars are called the anwā’ and the rising stars are called the ruqabā’8 • رقباء. The manāzil themselves are often described as subdivisions of these larger anwā’ groupings, and so there is a strong seasonal element to the interpretation of the lunar stations.

This seasonal element is often given in Arab culture as a naturalistic explanation of what the stations are and how they exert their influence on the world. Another seasonal element that we see in, for example, al-Buni’s Shams al-Ma’arif • The Sun of Knowledge, is the connection between the stations and temperament. Stations can be described as hot or cold, wet or dry, or even just temperate. All of these associations arise from a seasonal metaphor.

The connection between the stars and the seasons is extremely tenuous—it makes sense on the short span of human lives, but on the scale of centuries they fall apart. The “wet” stars that brought the seasonal rains to Yemen upon their heliacal set no longer co-occur with those rains anymore (and haven’t for centuries). The seasonal variations of temperature associated with a given station don’t happen during that station’s activation any more.

So what do we do about that?

It seems to me that the manāzil have always had a blend of stellar and seasonal attributes that are intrinsic to their nature. It’s not possible to extricate their sidereal and tropical traits from each other.

Maybe we shouldn’t try?

There are technical issues that arise as the solstices precess forward so we have to pick a method to ground ourselves in. The method that I have been lead to use myself is the sidereal one. Let’s leave it at that for now.

A final note against dessication

Dessication means “the state of being dried up,” something that I want all of my work to be a caution against.

A sidereal approach to the stations seems to be a relatively minority perspective, at least for those who use the tropical zodiac otherwise. There is a group of people using the sidereal nakshatras along with the tropical zodiac (Vic DiCara being a good entry point to their scene) but they are working with the 27 station Indian nakshatra system. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course! We selenophiles have so much to learn from the nakshatras!

But what I have been drawn to are the Islamicate manāzil, and a sidereal approach to them is in the minority. I want my work to provide an example of how we can investigate this system from a place of curiosity, but I don’t want to create my own dogmatic camp.

All of these approaches to the lunar zodiac deserve a seat at this table. Sidereal, tropical, constellational, all of them.

My goal is to contribute to growing shared gnosis. That requires a big table!

Really, all of these systems are cultural models for relating with the greater universe, which follows no such regimented order as the perfect Hellenistic ecliptic attempts to envision. Perhaps they have more value if they aren’t taken completely dogmatically but rather with an open-mind?

Our ancestors have taught us that the lunar spirits are shapeshifters. Working with them, the magician can produce a talisman for invisibility or a spell to open locked doors. These spirits detest borders and gatekeeping.

Perhaps we can show respect to this class of spirits and our inquisitive ancestors by disregarding borders too?

Take care,

Shuly Rose

Hart de Fouw & Robert Svoboda. 2011. Light on Life: An Introduction to the Astrology of India. Arkana.

Derek Walters. 2002. Chinese Astrology. Watkins.

Daniel Martin Varisco. 1991. The Origin of the anwā’ in the Arab Tradition. Studia Islamica, 74, 5–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/1595894

Shlomo Selah. 2009. Abraham Ibn Ezra The Book of the World. Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004179141.i-356. See section 62, p 93 (and Selah’s discussion on p 148)

see Book 3, Chapter 3 of William Ramesey’s Astrology Restored as a late 17th century English example or Planeten Buch for a late 16th century German one

The singular is naw’ • نوء and can mean “present” or “gift.” I think the metaphor is something like the storm clouds rising up in heaps bringing the gift of life.

Parans are a fascinating concept, far too complex to explain in this paragraph. The anwā’ and ruqabā’ aren’t exactly in paran to each other but I think it’s an interesting comparison to consider them as a kind of star grouping based on timing rather than apparent location. Check out this article for more about the history and theory of parans.

The singular is raqīb • رقيب. A raqīb is a guard or sentry—to me it seems like the anwā’ are disappearing, leaving the gift of rain in their wake, while the raqīb guard the stormy skies in their absence.

Great article! I will add that Olomi has mentioned that on the whole the calculations shifted to Tropical from Sidereal by the 11th century, but that they were still using both delineations for sidereal and tropical indicators. By the 10th century, he says that tropical mansions began to be used. Abu Ma’shar used tropical for horoscopes but sidereal for talismans, meanwhile Al Biruni used entirely tropical but Masha’allah used mostly sidereal. I definitely think the interpretations of the mansions can be both tropical and sidereal and we should use both!

“It seems like this question of sidereal vs tropical haunted astrologers for centuries. What a relief! We’re surrounded by ancestors”

Obsessed w this and you